At the College Art Association in February 2017 a colleague told me “This is your period.” Still in shock over the election results, I could not have anticipated how true his statement was. My book Visual Propaganda, Exhibitions, and the Spanish Civil War had been published four years before. Contrasting visual culture and exhibitions on both sides: the democratically elected republican Popular Front leftist coalition and the right-wing nationalist coalition that coalesced around the fascist General Francisco Franco, one of the leaders of the July 18, 1936 coup. Aristocrats, much of the Catholic Church, and the military were the backbone of the uprising. A key justification of the coup was that the democratic elections of February 1936 were rigged. I cannot help but think about my Spanish grandfather Vicente Basilio Bellver and his brother Jose, who served as representatives for their moderate left party at their polling place to certify the election results. Seeking information about my family, because I knew my grandfather fought against Franco, an archivist located the prison record of his brother. Sometime during or after the War, he was held at a concentration camp (their term) then a prison. When he was granted parole, the condition was internal exile — he could never return to the city where he was born. At another archive, I found the electoral documents where he and my grandfather signed off on the results. Their names were underlined in red. I can only assume that my grand uncle was deemed a grave danger because of his commitment to his party and participation in the electoral process.

I spent years trying to understand how the Nationalists created a cult of personality around Franco, whose dictatorship ended with his death in 1975. Their effort to craft his image was buttressed by imagery and ceremonies of absolute monarchy and the military, including photography, print culture, and Catholic iconography. Like President Trump, Franco was familiar to wide audiences. The latter appeared in newspapers and magazines that celebrated his military exploits in the Spanish colonies in North Africa and his role in the brutal suppression of a miners’ uprising in 1934. Depicted astride a white horse in photos, postcards, and a painting, he resembled Spain’s patron Saint James, known as the “Moor slayer,” entwining religious fanaticism, racism, and anti-leftist political views. I remember trying to explain Trump’s fame to friends in Spain, a reality-show star staging a simulacrum of entrepreneurship and corporate prowess. Since he could bend and bully aspiring entrepreneurs to his will and demonstrate his mastery of business, years later, he could convince many that he could “run” the United States. Similarly, Franco could apply his brutal military tactics to crush what he called the godless, leftist, Bolshevik, Jewish, Masonic enemies and restore order. Psychiatrist Antonio Vallejo-Najera, an admirer of Hitler and promoter of eugenics, warned against the anti-Spanish leftists, bearers of the degenerate “red gene.” Such strategies to dehumanize ideological opponents are familiar to us now. As we have seen, Trump has leveraged deeply rooted racist and anti-Semitic tropes and promoted new versions of witch-hunt tactics directed at progressives.

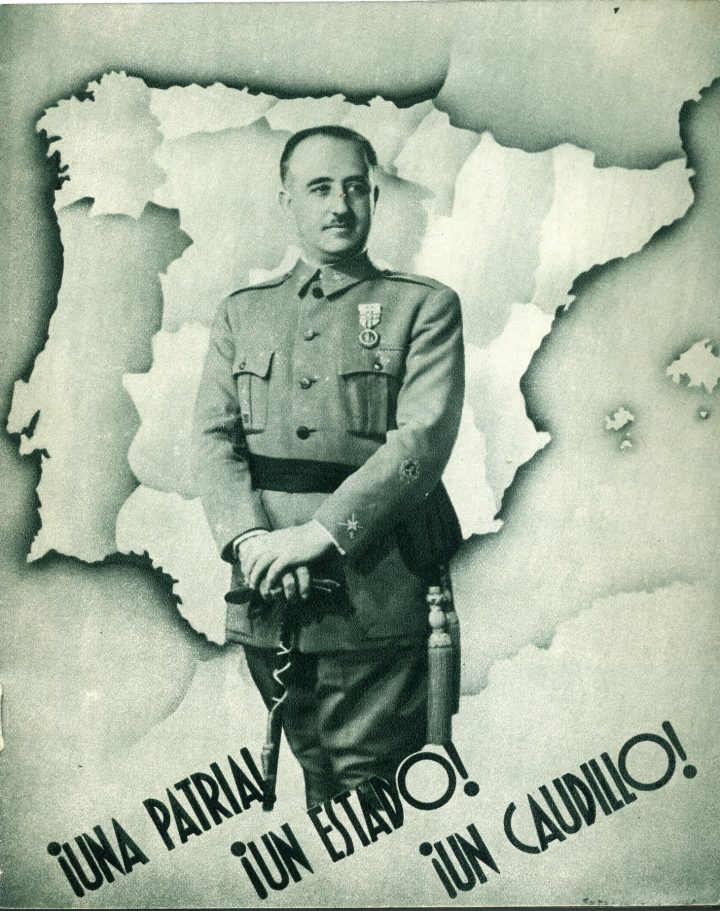

Like Trump, Franco’s appearance (short in stature, portly, with a high-pitched voice) was not that of a majestic ruler. However, the eventual dictator had a team of artists, writers, photographers, filmmakers, etc. who admired Hitler and Mussolini. They studied their propaganda methods and traveled to see posters, exhibitions, and ceremonies first hand. Illustrated magazines and newspapers disseminated photographs of the propaganda produced by Franco’s allies. In keeping with theorizations of advertising and propaganda that were discussed in Spanish magazines, Franco’s propagandists attempted to create an imposing image of the dictator, strictly controlling all images. They worked with Jalón Ángel, an official photographer known for his mastery of avant-garde photographic techniques used to enhance images of film stars. A kind of brand was created through the organization of distribution of postcards, photographs, and posters (these had to be on public view in government buildings, schools, prisons, and more) fawning news articles, and newsreels. Rendered ubiquitous, in some images, Franco was pictured looking at maps or in a photomontage where his body was placed over a map of Spain, embodying the nation. The slogan read: “One Fatherland, one State, one Military Leader,” emulating Hitler’s rhetoric.

Today, we have an even less majestic image of the leader’s body embodying the nation in Trump’s ever-present red MAGA hat. His incessant tweets also further his all-pervasive persona, an updated version of Mao’s pronouncements in the Little Red Book or big-character posters and murals. Many Trump propagandists are now looking to past autocrats, studying the ways in which they consolidated their grasp on power, undermined democratic institutions, creating chaos, promoting hate and violence. Trump’s dramatic appearance at the Truman Balcony when he returned to the White House from Walter Reed Hospital led to #Mussolini as a trending topic on Twitter. Trump’s escalating nationalist and violent rhetoric, the administration’s propaganda, and his anti-democratic tactics are leading many to recover history, finding parallels between Mussolini’s appearances on balconies and pairing the Nazi eagle symbol with Trump’s “America First” eagle design. My colleague was right, my scholarship on fascist propaganda, which I assumed would be of interest to a limited audience, is now chillingly relevant.

"general" - Google News

October 25, 2020 at 11:10AM

https://ift.tt/3krxlC9

When Photographers Created a Cult of Personality Around General Franco - Hyperallergic

"general" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2YopsF9

https://ift.tt/3faOei7

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "When Photographers Created a Cult of Personality Around General Franco - Hyperallergic"

Post a Comment