ALBANY — When Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo announced the creation of a powerful anti-corruption commission in 2013, William Fitzpatrick was by his side. The longtime Onondaga County district attorney is a Republican, but he and the Democratic governor shared a bond.

Cuomo remarked how after he was elected state attorney general in 2006, Fitzpatrick had gone out of his way to be helpful. “We went on for four years to have a really great relationship,” the governor said.

When Cuomo later faced intense criticism for meddling with the Moreland Commission to Investigate Public Corruption, Fitzpatrick emerged as his staunchest public defender.

Far less public was a controversy swirling around Fitzpatrick in the months before the Moreland Commission formed: A top official in the Syracuse Police Department, Shawn Broton, had gathered evidence concerning alleged malfeasance committed by Fitzpatrick's office — including seizing a recording of Fitzpatrick making an "off-color" speech; using a government crime lab to delete the recording; and threatening and intimidating the person who made the recording.

After Broton brought the evidence to the New York inspector general’s office — the state’s internal affairs unit — its investigators never interviewed the alleged victim or anyone else, according to records obtained by the Times Union. While the inspector general’s office issued two reports on related matters in the following months, including one examining the relationship between Fitzpatrick's office and the same crime lab, neither mentioned the most damning accusations.

“Shortly after all of this is going on, Fitzpatrick is appointed to the Moreland Commission,” Broton said in an interview with the Times Union. “You look at it, it’s just very suspicious timing.”

Fitzpatrick strenuously disputed there was any connection, telling the Times Union: "If your story says solely that the Inspector General dropped the ball on this because I'm friends with the governor, that is not only false, that is recklessly false."

In the years that followed, the inspector general's office would continue to be the focus of criticism, including other episodes in which key witnesses were never interviewed in matters related to Cuomo or his allies.

Following Cuomo’s resignation in August, state lawmakers are wrestling with how to reform internal controls that allegedly failed to check years of abuses. One particularly thorny issue: ensuring the state inspector general is independent.

Cuomo's resistance to independent oversight was a noted element of his professional life at least as far back as his tenure as secretary of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development in the 1990s.

In 1998, the agency's inspector general, Susan Gaffney, testified before Congress that Cuomo aides had once circulated an anonymous letter that accused her of racism, and sought to have her investigated. The career civil servant testified that Cuomo aides tried to have her audits issued through his own office rather than hers, and to smear her in the media.

Cuomo, she testified, was “uncomfortable with the concept of an independent inspector general who is not subject to his control.”

Since the creation of New York's inspector general in 1986 during the tenure of Gov. Mario Cuomo, the office's leader has been appointed by the governor. The appointee's term runs through the end of the term of the governor who made the appointment.

Under state law, the inspector general reports directly to the secretary to the governor. Good government advocates have for years pointed to this structure as inherently problematic: The inspector general is charged with investigating corruption, fraud and conflicts of interest in New York’s executive branch, which is run by the governor.

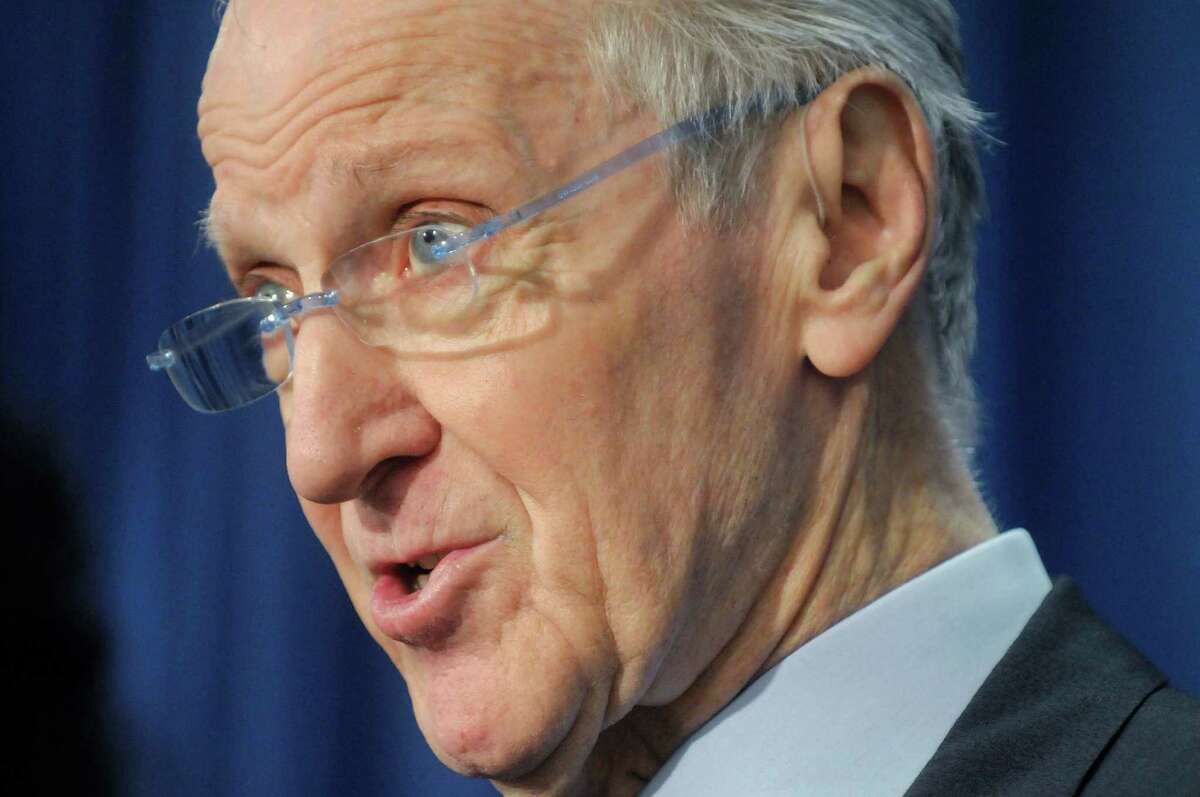

Still, the office has at times had a reputation for independence. Joseph Fisch, a Bronx state Supreme Court justice appointed by Gov. David Paterson in 2008, pursued several notable investigations into Albany's political elite.

State Inspector General Joseph Fisch at a 2010 press conference to release a report of the investigation regarding the selection of Aqueduct Entertainment Group to operate a video lottery terminal facility at Aqueduct Racetrack. (Paul Buckowski / Times Union)

Paul Buckowski/Times UnionBecause of his long personal relationship with Paterson, Fisch recused himself from his office’s high-profile probe into the bidding process to run the Aqueduct racino in Queens. A damning 300-page report, based on extensive interviews with top state lawmakers and lobbyists and written by Fisch's staff, included a section raising questions about Paterson’s own conduct.

"We pulled no punches — no fear or favor," Fisch said as he announced the findings in 2010.

‘Trusted allies’

Fisch, whose career in government began in the 1950s, retired after Cuomo's election as governor later that year.

The next three inspectors general were not at the end of long careers, and Cuomo's picks were all drawn from the ranks of his former staff at the attorney general's office. And the governor showed a penchant for appointing them to well-compensated landing spots after they stepped down.

Ellen Biben served as Cuomo’s first inspector general in 2011 and 2012, when she left to serve as the top staffer on the newly created state Joint Commission on Public Ethics. In 2015, Cuomo appointed her to a Court of Claims judgeship, an office carrying a nine-year term and a salary that grew to $193,000.

Biben's successor, Catherine Leahy Scott, ran the inspector general's office until the beginning of 2019. On Jan. 1 of that year — the first day after Leahy Scott’s term of office ended, which meant she could be replaced by Cuomo — Leahy Scott received a pay increase of more than $17,000.

But just five days later, she was out of the job. Beginning his third term, Cuomo announced the appointment of his longtime aide Letizia Tagliafierro. (Lee Park, a spokesman for the inspector general's office, said the $17,000 raise was a permissible "statutory salary increase.")

At the time, a Cuomo spokesman refused to say whether Leahy Scott was leaving voluntarily. She had, however, found herself at cross-purposes with the governor at least once in the previous year, when her office recommended disciplinary action against three top officials at the state Division of Criminal Justice Services related to allegations of sexual harassment, and the failure to properly address it.

Leahy Scott has never publicly discussed the circumstances of her exit. After five months as acting welfare inspector general, Cuomo appointed Leahy Scott to a Court of Claims judgeship, where she is paid nearly $211,000 annually with a nine-year term.

Tagliafierro took a quiet approach, never holding a single press conference. In the weeks since Cuomo's resignation, Tagliafierro remained as inspector general, drawing an annual salary of nearly $198,000.

But on Friday — a day after the Times Union asked Gov. Kathy Hochul's office whether she was keeping Tagliafierro — she tendered her resignation.

According to a Times Union review of the inspector general's website, the office never once posted a report stating Cuomo's Executive Chamber had been the subject of a critical finding. Instead, the three inspectors general trained their attention on lower-level offenders at often obscure state agencies and public authorities.

Among the higher-profile matters were a 2016 report on the Dannemora prison escape, and a 2016 report finding that a Republican state Board of Elections spokesman had leaked damaging information about New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio. The latter report was helpful to Cuomo by knocking down public speculation by de Blasio — a Cuomo adversary — that the information had been leaked by the Cuomo-appointed Board of Elections enforcement counsel.

In 2020, the office released an annual report, highlighting a probe into overtime abuse and vehicle misuse by a State Police task force, the severance package of a top Bridge Authority official, and $31,000 in personal spending of taxpayer funds by a SUNY official.

At times, the office has acted swiftly. In 2019, 12 days after receiving a complaint that the state’s government transparency advocate, Robert Freeman, had committed sexual harassment, Tagliafierro issued initial findings from the investigation, and Freeman was fired. Freeman was a nationally known proponent of transparency, and at times a critic of the Cuomo administration’s deficits in that area.

At other times, investigations have moved at a snail’s pace. More than three years after the Schoharie limousine crash that killed 20 people, the inspector general recently revealed it is still investigating the possible role played by Cuomo administration agencies in the disaster. Park called any comparison "apples and oranges," noting the Schoharie crash had been the subject of other investigations, while Freeman was quick to admit guilt.

An investigation into Cuomo’s former top technology services official, Robert Samson, took 32 months to complete. When the office finally referred possible legal violations committed by Samson to JCOPE, he had been out of state government for 11 months — leaving less than a month before jurisdiction to pursue the possible violations would expire.

For years, the office denied the Times Union’s requests for copies of the Samson report under the rationale that the investigation was “ongoing,” even though much of it was conducted in early 2018. In December 2020 — five months after Tagliafierro referred the matter to JCOPE — the inspector general’s office continued to claim there was an "ongoing investigation that has not yet been completed."

Park maintained the office was in "deliberative discussions" about the matter until earlier this year. The inspector general’s referral was finally provided to the Times Union in July.

That process was indicative of another pattern. While the office sometimes posts final reports of investigatory findings on its website, the inspector general in recent years has shielded certain findings from the public — even when the office had substantiated allegations of serious misconduct by high-ranking agency officials.

For instance, when Leahy Scott uncovered the allegations of sexual harassment at DCJS, those results were never publicized, and had been obtained by the Times Union from a confidential source.

Park called it "entirely false" that a state employee's rank determines whether a report is publicly released.

In another pattern of the Cuomo years, the inspector general's office failed to interview witnesses that might have confirmed allegations related to Cuomo or his allies.

Gov. Andrew M. Cuomo and Ellen Biben in 2011. She served as Cuomo's first appointed inspector general, and later became the top staffer at the newly created Joint Commission on Public Ethics. Cuomo later appointed her to the Court of Claims. (Michael P. Farrell/Times Union )

Michael P. Farrell/Times UnionDeleted files

On Dec. 15, 2011, Onondoga County's longtime district attorney threw a holiday party for roughly 70 members of his staff at Dinosaur Bar-B-Que in Syracuse. Mark Angiolillo, a local musician hired to perform at the event, videotaped part of William Fitzpatrick’s speech to the attendees. He would later tell Syracuse police that Fitzpatrick made a few off-color jokes, recalling one about “Black A Clause.” Fitzgerald has staunchly denied making any off-color remarks at the event.

After the speech, Angiolillo was approached by several high-ranking staffers in Fitzpatrick’s office, who asked for his cellphone and video recorder. The musician later told the Syracuse Post-Standard that an Onondaga County assistant district attorney told him, "If you don't give it up, we could have you thrown out the window."

In an interview with the Times Union, Fitzpatrick alleged his speech had been "illegally recorded" without his knowledge. He acknowledged that an assistant district attorney made "threatening remarks" to Angiolillo, but didn't know if that included a threat to have the entertainer thrown out a window. In any case, Fitzpatrick said he would not have considered such a threat to have been made seriously.

The next day, Angiolillo went to pick up the recording device at the district attorney's office. He said he was interrogated by Tim McCarthy, an investigator in Fitzpatrick’s office, for about 40 minutes. McCarthy allegedly brought up a domestic dispute case involving Angiolillo and his ex-wife that had occurred 18 years earlier.

“I was taken into a room and interrogated about my past history and things I had recorded,” Angiolillo said in a sworn statement. “They told me that I had police encounters over my ex-wife years earlier. They also asked me about the things on my recorder like a video of good-looking girls on the street ... all just nonsense things."

About six hours later, McCarthy returned the device. The footage of Fitzpatrick’s speech had been deleted.

McCarthy then stated, according to Angiolillo, “that what was on the device was a felony. ... He told me he had talked to the man — I took this to mean the DA himself — and that he was going to drop everything.”

Shawn Broton, who at the time was Syracuse's deputy police chief, learned about Fitzpatrick’s speech and the aftermath from an assistant district attorney in Fitzpatrick's office.

Broton believed several crimes may have been committed by Fitzpatrick's staff, including illegally seizing property and misuse of a government crime lab.

‘Close, personal friend’

Long-simmering tensions between the Syracuse Police Department and Fitzpatrick’s office escalated almost a year after the holiday party when Broton complained to a regulatory body about the district attorney’s alleged misuse of the regional crime lab, the Onondaga County Center for Forensic Sciences.

In a sworn police report, Broton wrote that Fitzpatrick told attendees at a December 2012 meeting of the county Police Chiefs Association that he was a “close, personal friend” of Leahy Scott. According to Broton, who was in attendance, Fitzpatrick added: “I can’t wait for them to come down and put Broton under oath.” Frank Fowler, then the Syracuse police chief, echoed Broton's recollection of Fitzpatrick's comments, but remembered them occurring at a meeting with local judicial officials.

Fitzpatrick said those recollections were "total bull----" and that he never made those remarks.

Broton was soon contacted by an investigator in Leahy Scott’s office and was interviewed. The investigation was launched upon the request of the state Commission on Forensic Science, which had learned of the Syracuse Police complaints, Leahy Scott's office has stated.

On Feb. 28, 2013, Broton drove to Buffalo for a second interview, and laid out new allegations about the Dinosaur incident. Because Leahy Scott’s office was already investigating Fizpatrick's relationship with the Center for Forensic Sciences — and the recording of Fitzpatrick’s speech was deleted at the same crime lab — Broton viewed the new information as relevant to the ongoing inquiry. He provided the inspector general’s investigators with a copy of signed statement by Angiolillo and the name of the whistleblower in Fitzpatrick’s office.

The two officials from the inspector general’s office, senior Investigative Counsel Jeffrey Hagan and Investigator Charles Tirone, did not ask Broton follow-up questions about much of the information he recounted. Instead, their questions centered around Broton’s own investigative methods, according to an audio recording of the interview.

Broton never heard from the inspector general’s office again. But in an April 2013 report, Leahy Scott’s office found there had been "no serious negligence or misconduct" committed by the crime lab.

A second report, issued about three weeks after Fitzpatrick was named by Cuomo as the Moreland Commission's co-chair, was critical of the Syracuse Police Department, and concluded a detective may have violated state law by using an unaccredited lab to test evidence.

Neither report said a word about the Dinosaur restaurant incident. Angiolillo, the alleged victim, was never interviewed, he confirmed this week.

In response to a Times Union open records request, the office provided 133 pages of witness-interview notes taken while compiling the reports. Those documents never mention the Dinosaur incident. After the Times Union pointed out that the Feb. 28, 2013, interview with Broton was missing, the inspector general’s office provided a copy of those notes, stating the office had “inadvertently omitted” them.

The inspector general’s office interviewed Fitzpatrick on Feb. 5, 2013, about a number of issues related to the crime lab. But the inspector general’s office did not later ask Fitzpatrick about his holiday party speech.

Fitzpatrick told the Times Union there was "no reason" for him to be interviewed, since he was not present for the alleged incidents between his staff and Angiolillo.

Fitzpatrick said Leahy Scott's office did not have jurisdiction to investigate a district attorney, especially to determine whether "an elected DA directed a DJ to be thrown out a window."

In its April 2013 report, the inspector general's office did examine the relationship between Fitzpatrick's office, the Center for Forensic Sciences, and the lab's handling of forensic evidence. According to the report, the inspector general has jurisdiction to pursue “allegations of serious negligence or misconduct" substantially affecting the "integrity of forensic results" of any laboratory system.

The report added that, even when the inspector general's office did not have jurisdiction over certain alleged conduct, all of Broton's allegations were investigated anyway, since public confidence in the crime lab was paramount.

The report discussed eight categories of allegations made by Broton, finding they could not be substantiated. Yet the report did not mention the most serious allegation, concerning the deletion of Fitzpatrick's speech by the crime lab. All the allegations made by Broton were not investigated, despite the report's assertion to the contrary.

Park noted the specific allegation regarding a video recording "was raised after the bulk of the investigation was complete."

"It was determined to be beyond the inspector general’s jurisdiction," Park said. "However, a complaint regarding this allegation was also filed with the (state) attorney general’s office [by Broton]. The inspector general’s office confirmed this and deferred to the attorney general’s office for further consideration."

If the inspector general’s office had pursued the Dinosaur allegations, they might well have found hard evidence. Broton later obtained computer notes taken by a technician at the crime lab, written the afternoon after Fitzpatrick’s speech. The lab technician stated that McCarthy, the investigator from Fitzpatrick’s office, had sought help in scrubbing all videos and photographs from a recording device, the same brand as the one Angiolillo owned. The date and time of the deletion match up with Angiolillo’s account.

Fitzpatrick told the Times Union that he was unaware of the lab technician's notes, but said such a deletion request would not be "unreasonable," since his speech had been "illegally recorded at a Christmas Party." Fitzpatrick declined to address whether using a government lab to delete a seized video recorder would be a legally appropriate procedure.

Fitzpatrick said Broton was "incompetent," had unsuccessfully sought investigations from "six different agencies including his own," and that his own Syracuse Police investigators had "laughed at him."

Broton confirmed that he also contacted he FBI, which lacked jurisdiction, as well as the state attorney general's office, the state Joint Commission on Public Ethics, a state Supreme Court judge, and the State Police. He said two Syracuse Police investigators had declined to pursue the matter, but only because they regularly worked with Fitzpatrick's office and feared retaliation.

Fitzpatrick said he never discussed the Dinosaur incident with Cuomo's office, and that Cuomo asked him to serve on the Moreland Commission in July 2013, two months after the inspector general report on the crime lab.

The Moreland Commission prompted far more controversy. In the fall of 2013, Fitzpatrick — at the urging of a top Cuomo aide — agreed to pull back a Moreland Commission subpoena aimed at a media-buying firm that had placed millions of dollars in ads for the Cuomo-controlled state Democratic Party. In March 2014, Cuomo announced the commission would close down midway through its planned 18-month lifespan.

The following month, Fitzpatrick penned an op-ed in the Huffington Post defending the governor’s actions. “My focus is on the good that Moreland accomplished,” he wrote.

Unanswered questions

Spencer Freedman, second-in-command at the inspector general’s office from 2012 until he left the job in February, oversaw the Onondaga County investigation in 2013. Six years later, Freedman again led a probe where key witnesses were not interviewed.

On Jan. 29, 2019, JCOPE had been forced by court order to vote on opening an investigation into whether a former top Cuomo aide, Joseph Percoco, had illegally used government resources while managing Cuomo’s reelection campaign, and whether Cuomo had known about the illegality.

Soon after the closed-door JCOPE vote, Cuomo called state Assembly Speaker Carl E. Heastie and berated him about how Heastie’s commissioners had voted on the Percoco matter. That indicated that someone within JCOPE had illegally leaked to Cuomo — or to an intermediary — information about the confidential vote.

JCOPE’s executive director reported the leak to the inspector general’s office, which was required by law to investigate. But the inquiry languished. As the months dragged along, unrest grew among some commissioners. In September 2019, at least one JCOPE commissioner threatened to go public.

Letizia Tagliafierro during a 2013 meeting of the state Joint Commission on Public Ethics. She recused herself from a 2019 investigation of a leak from the ethics panel to Cuomo; the governor was never interviewed. (John Carl D'Annibale / Times Union)

John Carl D'Annibale/Times UnionA few weeks later, the inspector general’s office issued a three-page letter to JCOPE’s commissioners that stated the leak allegation had not been substantiated. But it later emerged that key witnesses, including Cuomo and Heastie, had never been interviewed.

The law governing the inspector general’s office requires all state employees to “report promptly to the state inspector general” any information concerning corruption or criminal activity. Failure to report such activity is "cause for removal from office" or "other appropriate penalty." Neither Cuomo nor Heastie reported any knowledge of the apparently illegal leak.

After the Times Union reported on the leak in November 2019, the inspector general's office argued that no one outside JCOPE had needed to be interviewed, since only the possible leaker within the agency faced potential legal liability. But the inspector general’s office — like all investigative bodies — routinely interviews witnesses that do not face legal peril.

Tagliafierro recused herself from the leak probe, citing her former staff position at JCOPE. The investigation was handled by Freedman, who like the inspectors general he reported to, had worked under Cuomo when he was attorney general.

He left the inspector general's office in February for a job as special counsel and senior adviser to State University of New York Chancellor Jim Malatras, a longtime Cuomo confidant who has himself been embroiled in several of the former governor’s controversies. Freedman's new job came with a raise of more than $13,000; he is paid an annual salary of $185,000.

Park said the three inspectors generals' long professional relationships with Cuomo hadn't impacted them, adding the office has a "robust recusal policy." He said the those inspector generals and Freedman were "public servants who have done outstanding work for the state for more than a decade" and have "rightfully received promotions that do not influence how they conduct themselves."

Asked if the office ever avoided gathering damaging evidence about Cuomo or his allies, Park called the question an "affront to the dedicated state employees of the inspector general’s office who are charged with protecting the public’s interest."

Freedman, Biben, Leahy Scott and Cuomo all declined to answer questions.

Guardrails

On her first day as governor, Kathy Hochul promised sweeping reforms to New York's ethics oversight system. Just a day later, the state Senate's Ethics Committee held a hearing on the topic.

Much of the attention was focused on JCOPE, which has been the subject of regular media criticism. The inspector general’s office has gotten far less attention.

Tagliafierro declined to testify before the committee. Her spokesman claimed no one in the office was available to answer questions from lawmakers, who were eager to know more about the lackluster leak investigation.

Blain Horner, executive director of the New York Public Interest Research Group, testified that some states require two-thirds of both houses of the Legislature to confirm an inspector general. In New York, there is no confirmation required by either chamber, creating few checks on a governor's desire to install a loyalist.

Horner said the law requiring the inspector general to report to the governor’s secretary should be amended, and that the law should create greater insulation from political blowback.

Lawmakers and good-government groups floated other ideas, including for the independently elected state attorney general, or perhaps the state comptroller, to be in charge of appointing the inspector general, instead of the governor.

Senate Ethics Committee Chair Alessandra Biaggi, a Democrat, peppered witnesses with questions about how to reform the office. While easy answers were not apparent, Biaggi said she was focused on making the office independent.

“So what are the guardrails we can put around this, to make it strong?" Biaggi said. "Because clearly this is a very powerful role in our state, and hasn’t been doing its job — and so we have to do ours.”

"general" - Google News

September 19, 2021 at 05:07PM

https://ift.tt/3koZH2m

The state inspector general's oversight waned under Cuomo - Times Union

"general" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2YopsF9

https://ift.tt/3faOei7

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "The state inspector general's oversight waned under Cuomo - Times Union"

Post a Comment